"She told me: she’d like to meet the mother who endures childbirth, six times over, for some 'food stamps that barely last the month.'”

A regular installment about race and money in America, from the authors of "The Black Dollar"

As authors of the forthcoming book, “The Black Dollar,” we are studying the history of race and money with a focus on Black Americans.

In our ongoing newsletter, we bring you a regular Q&A that we hope will spur conversations in your household, and, at the end, we highlight online stories or resources that we think are worth your while.

The Q&A.

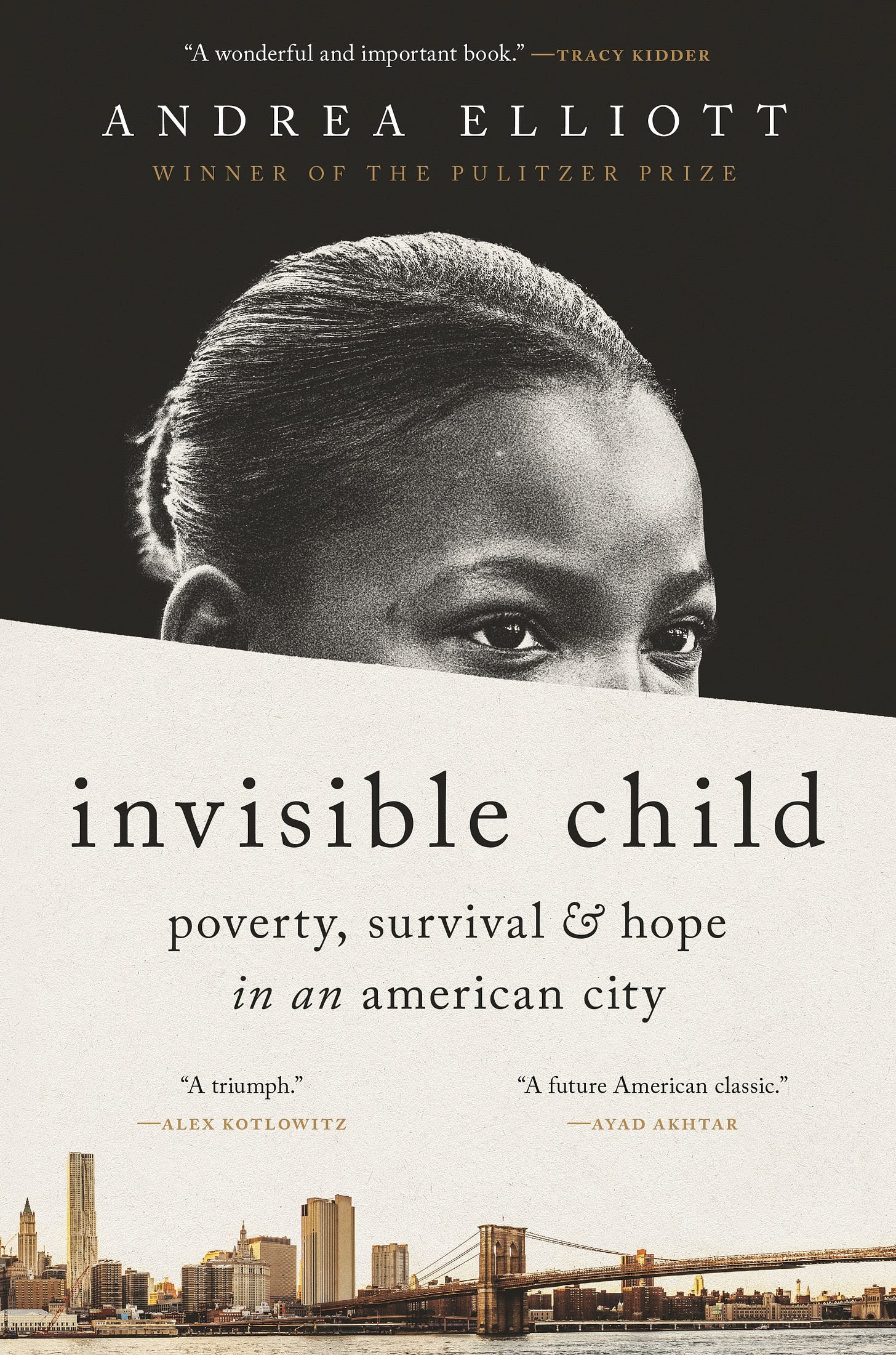

“The Invisible Child,” Andrea Elliott’s new book, is about “poverty, survival and hope in an American city,” according to its jacket. But woven in throughout the storyline are details that speak to race and money - the topic that Ebony and Louise are focusing on in their reporting.

Louise sat right near Andrea as she began reporting on Dasani in 2012 at The New York Times. So, on a personal level, Louise was happy to see the product of Andrea’s long, dedicated, careful reporting come out in this important new book.

Louise caught up with Andrea earlier this week …

Louise: Andrea, congratulations on a wonderful book. It illuminates so many things in our society, but I’m going to focus on the elements around money.

The book is about a family of ten -- two parents and eight children -- living mainly in homeless shelters around New York City. The main character is Dasani Coates, who you met when she was 11 years old in October 2012. At that time, you took note of the family’s budget. Walk us through that...

Andrea: People have a lot of misconceptions about the poor and their relationship to money: that they don’t want to work, for example, or that they are constantly gaming the system. Dasani’s family showed me a different picture. When we met, they were getting $65 a day in public assistance. This came down to $6.50 a day per family member – barely enough to cover a subway trip and a gallon of milk. They could have received much more money had they applied for the disability benefit known as SSI (at least two of the children would have qualified), but Dasani’s parents did not want their children to get marked as disabled, for fear they would internalize the label. Both parents were in drug-treatment programs and struggled to find jobs in the formal labor market. Yet they worked every day, relying on a vast network – the underground street economy – to bring in a few extra dollars by selling pirated DVDs or doling out freelance haircuts. The children pitched in collecting cans and bottles for recycling. For any family living on the edge, every dollar counts.

Louise: There’s a scene in the book where Dasani’s family gets a tax refund. It’s a big event to have an infusion of a few thousand dollars. Tell us about that money - how did Dasani’s family earn it, why was it refunded and did they get to keep it?

Andrea: In Dasani’s Brooklyn, January is known as “tax season.” It’s when poor parents rush to file for special tax breaks given to low-income families, such as the Child Tax Credit and the Earned Income Tax Credit (EITC). These IRS programs distribute cash subsidies – commonly referred to as “refunds” – that lift millions of Americans out of poverty every year. What’s notable is that Dasani’s parents had not filed for a refund in years. They only did so under pressure from their homeless shelter, which in 2012 made them sign a contract agreeing that if they did not file for their “refund” they could be forced out of the shelter. And why was that? Because the shelter system, according to state law, is only meant to be temporary. A family must save enough money to leave. That year, Chanel got a $2,800 tax credit in cash, which was far less than what the family needed to rent a place and move out. Supreme’s credit was seized by the state because he owed child support to two women.

Louise: I was struck by some of the more separate measures the family took to get money. Some involved teeth.

Andrea: Money is security. Without it, people are pushed to the brink – especially when they have children to feed. When Dasani’s mother Chanel was still a teen, she, Dasani’s grandmother, an aunt and a cousin all agreed to have their teeth pulled by a dentist as part of a Medicaid scam. He was offering $1.25 per tooth, in cash. She told me what happened in wrenching detail: how two strangers held her down as the dentist pulled her teeth without numbing the pain. To corroborate Chanel’s story, I searched her Medicaid records and there it was: In 1994, a Brooklyn dentist billed Medicaid $235 for pulling four of Chanel’s teeth. Who gets four teeth pulled in one day? She remembers losing only two teeth, which means that he probably lied to Medicaid while only paying Chanel half of the $5 she was owed.

Louise: And then there were the food stamps. Dasani and her siblings knew when they were coming almost like their own birthdates. Did you find that food stamps covered their hunger and worked smoothly?

Andrea: Out on the street, the sheer size of Dasani’s family drew attention. Strangers often stared with judgment, perhaps seeing Chanel as a “welfare mom” who had kids to profit from the system. I’ll never forget her response: She told me she’d like to meet the mother who endures childbirth, six times over, for some “food stamps that barely last the month.” More than 40 million Americans rely on food stamps, which tells you a lot about the state of our country. It’s an essential benefit, but the delivery of this program is often unreliable (despite how many children desperately rely on it). Food stamps work best when a family has access to a working kitchen, which allows for the planning of meals. Dasani’s family lacked that privilege, which meant that their food stamps quickly vanished with store-bought meals.

Louise: You traced Dasani’s family back several generations and as time passed in the book, we see welfare programs changing. How much did the changes, like Clinton’s work requirement, affect the family and was it a positive or negative effect as you look back with the longer lens?

Andrea: Any policy shift has its cheerleaders and its detractors. I felt it wasn’t my role, in reporting and writing this book, to take a major policy position. It was to tell the story of Dasani’s family against the backdrop of history. And for Dasani’s grandmother Joanie, welfare reform brought a sea change. She got sober, entered a welfare-to-work program and landed a stable job for the rest of her life, leaving behind a pension of $49,000. She became Dasani’s ultimate role model because of her own reformation, which was connected to welfare reform. But plenty of other women had starkly different experiences, especially those who were disconnected from both welfare and work.

Louise: Going back even further, you wrote about how Dasani’s great grandfather was a talented mechanic, but back in the 1950s in Brooklyn, many mechanics jobs weren’t open to Black workers. Tell us about his experience and how that affected his earnings.

Andrea: A pivotal moment in the financial trajectory of Dasani’s family came when her great grandfather, June Sykes, landed in Brooklyn after WWII, after surviving three major battles in Europe. As a military veteran, June qualified for the same GI Bill supports that lifted millions of white veterans into the middle class -- college scholarships, job training, mortgages and business loans. But those doors were largely shut to Black veterans, so June settled for a very different life. He remained a renter, living in public housing. He never went to college. He was a trained mechanic, but found only menial jobs, pouring concrete and mopping floors. For perspective, Black janitors earned 41 percent less than white mechanics. The gap between those two incomes, over 20 years of June’s working life, came to $192,000 of lost earnings in today’s dollars.

Louise: Some of the experiences that Dasani’s family has could be had by a family of any race. How is homelessness different for a Black family and how do you think about race as a factor in the lives of Dasani and her family?

Andrea: Homelessness is a tragedy for all families, but Black Americans have been disproportionately hit. They account for 13 percent of the US population, but 39 percent of homeless people. Race is a major part of this story. Dasani’s family became homeless in the absence of a strong safety net – both public and private. We don’t talk enough about the private safety net that enables many white families to endure something like the pandemic, or to survive a major medical crisis. That safety net is usually tied to real estate, which is where race comes in. Back in the 1950s, restrictive covenants, redlining and other racially exclusive practices kept Black Americans out of real estate at a time when home ownership was key to creating intergenerational wealth. White families were able to amass ten times the net worth of Black families. All of these historical threads are tied to Dasani’s current plight.

Louise: Thank you Andrea.

The Latest Highlights.

On Race and Unions: As we’ve interviewed Black Americans for our book “The Black Dollar,” one piece of family history that’s come up numerous times is the difficulties some people’s parents and grandparents had with labor unions. Though the labor movement represents workers’ rights, they haven’t all welcomed all workers in the past. In fact, in 1935 when the National Labor Relations Act was passed granting rights to unions, the AFL successfully lobbied to remove a provision that would have required unions to grant membership to Black Americans. It was not until 1964 that the National Labor Relations Board said that unions could not block Black Americans from joining. That change in 1964 was good, of course, but it didn’t make up for decades where Black Americans — like Dasani’s great grandfather in Brooklyn — were making less money than they could have.

So, given this history, we have been discussing this New York Times story by Eduardo Porter about Boston’s struggles to employ minorities on its building projects. It features the former head of the Boston Employment Commission, who resigned last month exasperated by the lack of progress. “A councilor got up to say this is a union city,” that former Boston official told The Times. “For me, he was saying this is a white city, a city for white workers.”

Is Race and Money Connected to Sewage?: Here’s a surprise nugget for you from our book reporting. Tickets and fines related to sewage and trash collection violations are common among Black Americans. We have not yet gotten to the bottom of why and the answer likely varies by geography. But a new case in Alabama got our attention. Here’s a write-up about it from a non-profit advocacy group. As Catherine Flowers, the founder of the Center for Rural Enterprise and Environmental Justice, put it: “Sanitation inequality is one of the last vestiges of the Confederacy.”

Journalism, Race and Money: In addition to our work reporting about race and money, we both are keenly interested in seeing the news industry add more diversity in its coverage and on its journalism teams. This ties to race and money because news outlets play a significant role in the public’s understanding of racial and economic inequality. So, we always take an interest in new data points coming out that are relevant to journalism and diversity. This week, we note that Ernesto Aguilar, a public radio programming director, has posted new slides about audio consumption showing that “multicultural listeners” are more likely than white to listen to radio, podcasts and audio books.

Ping us anytime with your thoughts about race and money, and follow us on Twitter here. (It’s a brand new account!) And share this newsletter with your friends.

-Louise and Ebony