"There are so many people in the business community who ... don't understand capitalism," says a Civil Rights leader. "They think that in order for them to have more, the poor have to have less."

A regular installment about race and money in America, from the authors of "The Black Dollar"

On this Martin Luther King Jr. weekend, we bring you a post about some of Dr. King’s views about the racial wealth gap.

First, an image from the road:

The Q&A

“Frogmore” stuck out in the interview we had with civil rights leader Andrew Young last summer.

Andrew partnered with Dr. King in the 1960s and went on to be the U.S. ambassador to the United Nations and a two-term mayor of Atlanta, Georgia.

We spoke with Andrew at length last year and wanted to share a part of the interview that covered Dr. King’s focus on economic injustice.

This is where we learned of Frogmore.

Ebony: So in the late 1960s, you and Dr. King were focusing on economic injustice. Tell us about the connection between race and money as you and he saw it.

Andrew: Slavery was about money. Slaves were actually monetized. So they were a “money.” One of Martin's phrases was: it's a cruelty just to monetize a people as money and don't let them make any themselves.

Louise: Right, he said Black Americans were given a “bad check.”

Andrew: Yeah, that was in the March on Washington. That the Negro was given a bad check. Yeah, and it came back marked “insufficient funds.” But now that wasn't exactly true because there was a group of preachers who went to see General Sherman down in Savannah, but that didn't pan out well. It did not pan out, and it didn't pan out because Lincoln was killed three days after he signed it.

Ebony: You’re referring to the initial promise the United States made to freed slaves after the Civil War to give them 40 acres and a mule, which was cancelled soon afterwards. Many Americans do not realize how close our country came back then to offering a form of reparations to the freed slaves.

Andrew: Right.

Louise: Was there a time in your life when it clicked, that money is as important as other Civil Rights issues?

Andrew: It was more gradual. My parents had just enough money to get me to college. They didn't have a car when I was growing up. They paid my way to college, but they were always very proud about money. One of the things I keep remembering is when my dad showed me a bar of Ivory soap. I don't know how old I was, 10, 12. He said, “see this Ivory soap bar? One hundred percent pure.” He said, “that's pretty clean, pretty good. That's not good enough for you. You’re Black. You cannot cut corners. Period. Right, full stop. If you cut in the corner, they will find you and charge you with something.”

Louise: So the earliest thing you remember on the racial gap is being told there's a difference in how you’ll be judged.

Andrew: Yeah, I couldn't have been more than 11 and 12. I ran to the grocery store. Two blocks away to get - I don't know what I went to get, but they gave me five dollars to pay for it and the butcher gave me the change for five dollars, but gave me the five dollars back. And I came back and gave the money back to my dad, and he just started taking off his belt.

Louise: He gave you a spanking?

Andrew: No, he said you have five minutes to take it to get back there and apologize and get back here. But I mean, there was just no compromise right - any dishonesty was stealing, right?

Ebony: On race and money, you played a big role in wooing companies to Atlanta in the 1980s and also for the Atlanta Olympics. What do you think today of all the corporate pledges to change today — to support more Black-owned businesses and foster more diversity in business?

Andrew: Yeah, I mean, I've seen the announcements. But are they really real? You still have to see it. It really pains me that there are so many people in the business community who — how do I put it — they don't understand capitalism. They think that in order for them to have more, the poor have to have less.

Andrew: I made the argument in Birmingham that, look, the pie gets bigger — and you get a bigger piece of the pie — when you let other people into the pie.

Louise: That is something you pushed as mayor of Atlanta, by expanding the minority contractor requirements. But let’s pause on the pie because there’s been a long-running discussion, a debate of sorts, about whether the path forward is for Black consumers and Black business people to get in on already-established pies or whether they should essentially make their own pies.

Ebony: Yes, in fact, in Dr. King’s last speech, “I Have Been to the Mountaintop,” there is a section that had to do with race and money.

As you know, “I Have Been to the Mountaintop” was Dr. King’s last speech, delivered in Memphis the day before he was assassinated in 1968. Usually, people focus on Dr. King’s conclusion where he says “I've been to the mountaintop … And I've seen the Promised Land. I may not get there with you. But I want you to know tonight, that we, as a people, will get to the Promised Land.”

But about race and money, there is a section mid-way through the speech where Dr. King called for people to shop with Black-owned businesses and to “bank-in” and “insurance-in,” avoiding white-owned businesses that were not treating Black Americans well.

Andrew: He talked about a lot of things that people are talking about now. He was talking about a guaranteed income, a guaranteed annual income.

He first gave most of that speech - “I Have Been to the Mountaintop” — about a year before.

Louise and Ebony: Really? Where?

Andrew: In Frogmore, South Carolina. It was a Quaker place, a place that we used to go to relax.

—

The Journey

Louise wanted to learn more about Frogmore, so she visited it while driving up the Eastern coast. Here’s what she learned there:

In 1967, just after Thanksgiving, Dr. King and his team went to Frogmore, South Carolina, for a retreat.

Frogmore is an unincorporated section of Saint Helena Island in South Carolina. It’s named after a fish stew. It is the seat of the Penn Center, a historic school built by Quakers for freed slaves after the Civil War. The Penn Center continued to educate local Black Americans until the mid-1900s, because, locally, they were not fully included in the public school system until then. In the 1960s, it was an important retreat for Dr. King, Andrew Young and others in their group. They made many visits here including one in the early 1960s, when Dr. King wrote his “I Have a Dream” speech during his visit.

The 1967 Frogmore retreat is important to our ongoing research. It was Dr. King’s fifth and final meeting of the Southern Christian Leadership Conference at the Penn Center.

There, Dr. King spoke about pushing the Civil Rights movement in a new direction — to focus on a more radical redistribution of money and power. “Something is wrong with capitalism as it now stands in the United States,” he said.

At that gathering, he formulated his priorities for 1968 including The Poor People’s Campaign, which he would announce in January, meant to be a caravan of poor people converging on the nation’s capital. He began forcefully pushing for a national guaranteed annual income as well as more focus on jobs and affordable housing.

Months into planning all this, in 1968, Dr. King was killed on April 4,1968. One wonders how the Civil Rights movement would have been different had he lived to carry out his push for economic equality.

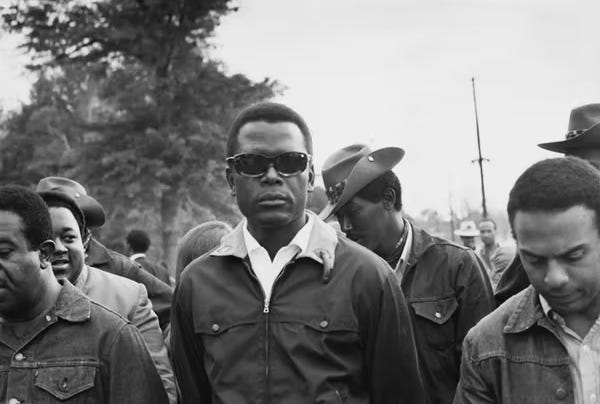

Last weekend, after actor Sidney Poitier passed away, Bernice King — a lawyer and minister who is the youngest daughter of Dr. King — posted this photo on Twitter:

It’s a photo of Sidney Poitier (middle) and Andrew Young (right) a month after Dr. King was shot. They were carrying out the Poor People’s Campaign march in Washington.

—

Honoring Dr. King this Year.

Here are some online resources for honoring Dr. King this year, virtually.

“Eleven Virtual Events to Celebrate MLK Day with Your Kids.” Tinybeans.com

"Civil Rights Museum: Virtual Celebration.” The Memphis Civil Rights Museum.

“MLK, Jr. Beloved.” The King Center.

—

The Latest Highlights.

Congressional Slaveowners. The Washington Post created a fascinating database of members of Congress who owned slaves. They show how very common it was for our country’s leaders in the early days to own slaves, and how the tie to slave ownership continued within Congress well into the 20th Century.

Reparations in Evanston, Ill. A story in Crain’s Chicago Business explores how Evanston’s new $10 million reparations program may work.

A Growing Gap. A Zillow analysis found that the gap between white and Black Americans in terms of getting a mortgage loan has grown during the pandemic, Marketwatch reports.

Paying for their Own Foster Care. The Marshall Project features a video about a woman in the Alaska foster care system who found that the state was collecting the benefits that were owed to her. While foster care is a difficult economic issue for all races, Black children represent 14% of the total child population but 23% of all kids in foster care. The foster care system was a major part of the book “The Invisible Child” whose author we featured in an earlier newsletter.

An Interesting Game: This video game explores racism in the U.S. housing system. It’s an interesting way to think through historic and current issues on this topic and to share them with kids learning this history. Here’s a write-up about it from Bloomberg. A special thanks to a reader of our newsletter — Guthrie Collin — who shared this with us to share with you.

Don’t Miss This: Sidney Poitier and Civil Rights. This is a interesting column about Mr. Poitier’s ties to the Civil Rights movement, written by Aram Goudsouzian, who is an author of a book about the actor. It includes how Mr. Poitier, in his 1967 speech for the SCLC, said that Dr. King “has made a better man of me.”

—

Thanks for reading. If someone forwarded this to you, hope you’ll sign up to remain on our list!

- Louise and Ebony (More information about us can be found here. This newsletter will be running every other week. See you in two weeks.)

It is challenging to think about what the assassination of Lincoln, of Martin Luther King and others has cost this country. How different would we be today if reconstruction and ‘forty acres and a mule’ had been fully realized, if MLKs dream had been a national value? It boggles the mind to think how close we came to being a more just society. Thank you for your well written informative articles.